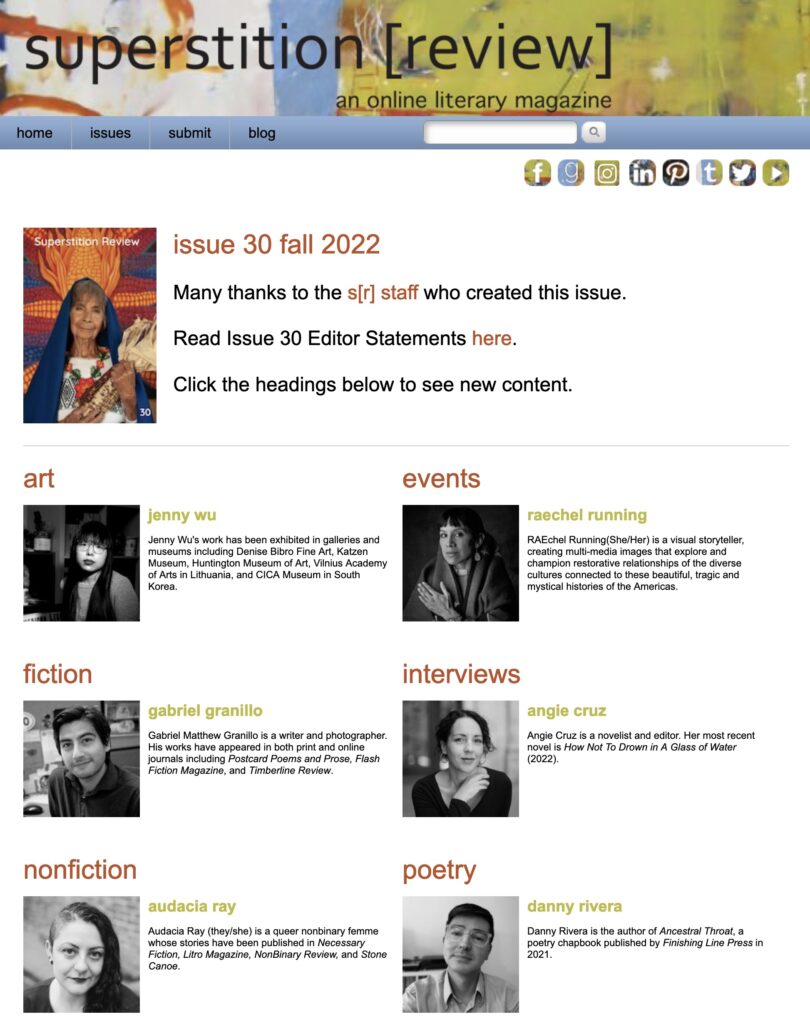

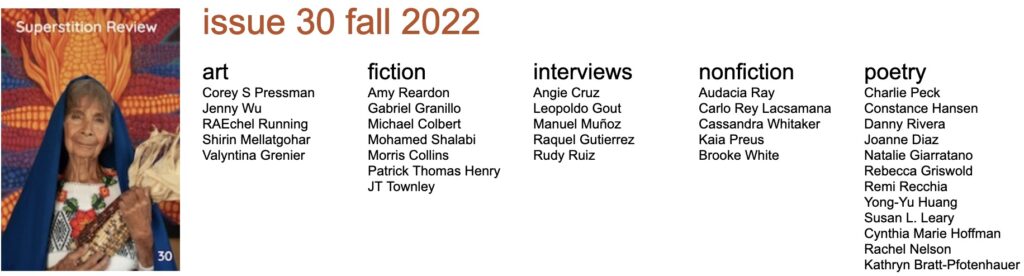

Benjamin Faro’s poem, “A Party of One and Many,” is forthcoming in Nimrod Journal. A brief but moving piece on grief and reminiscence, it was chosen by Amsterdam University College’s creative writing students to be the focus of an interview with Faro. They have also curated a variety of questions for Faro about “A Party of One and Many” and his writing process. We are pleased to include those questions and Benjamin Faro’s responses in an interview below. Due to the time difference, this interview was conducted by Brennie Shoup, Superstition Review’s blog editor. Read more about the collaboration between AUC’s creative writing students and Superstition Review here.

Benjamin Faro is a green-thumbed writer and educator living in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on stolen Taíno lands. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Equatorial, an international curation of undergraduate poetry, and is also pursuing his MFA in Creative Writing at Queens University of Charlotte, where he serves as Poetry Editor for Qu Literary Magazine. His poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared or is forthcoming in a number of literary journals, including Atlanta Review, EcoTheo Review, Interim Poetics, JMWW, Portland Review, West Trade Review, and others. Learn more on his website.

Brennie Shoup: Hello! My name is Brennie Shoup. I’m Superstition Review’s blog editor, and today I will be interviewing Benjamin Faro on behalf of the Amsterdam University College Students, who have curated a variety of questions about his piece, “A Party of One and Many” (I believe [this] is the title of it). And they were super happy to read this poem, and they wanted to talk to him about the process and his work. So, would you like to introduce yourself?

Benjamin Faro: Yeah! Sure. So my name’s Benjamin Faro, and, you know, this is a piece I wrote over this past summer. And so it’s relatively recent, and I’m really grateful for the questions that the students sent and for this opportunity.

BS: We are so happy to have you and so happy that you agreed to do this interview. We’re so excited to see what you say about your process and all that. I’m sure the students are really happy about that, too. So, getting into the first question: what inspired you to write this piece?

BF: Yeah, so, recently—within the last few years, I would say—a number of people in my life have passed away, unfortunately. And as people do, we sit with that, and we think about that. We think about those people. And even after the writing of this piece, another person close to me passed away, and one of the unique things about it—all of these people liked to cook. They’re people that I know from the kitchen, which, of course, is where the poem is set.

Thinking about those things, and thinking about how—as you get older—the more people you know will pass away. That number accumulates, and then you find yourself thinking about, “Oh, it’s the anniversary of so-and-so’s death, and this person’s death.” And thinking about that in terms of a celebration. I realized I can bring these people together in one space, like as I was cooking and thinking about all of them. And, interestingly, in a way that probably would never have happened if they were alive because they lived in such different places… [I was] really just sitting with the idea of having all of these people with me in the post-life.

BS: Yeah, I think the poem definitely has that sort of unity, and I think it really comes through. And the title of this piece specifically—and maybe your poetry in general—how do you decide on those titles or on a title for a work?

BF: I’ve been thinking about titles… It’s been a focus of mine in my work over, I’d say, the last year or two—and really trying to—you know, of course, maybe not all of my titles achieve this or reach this end… But I really try to make all of them do some kind of work, whether that’s contextualizing the space in which the poem is embedded or initiating a narrative or something like that. Or just stimulating some kind of contemplation. And I think that’s why this title went a little bit… hinting that there’s an ambiguous number of people here—or number of entities, at least. That hinting at that idea of celebration with “party” and playing on that word… Yeah, sometimes you just land on a—I don’t know—as with poetry… I know that I wanted it to do something there, and this is what I landed on.

BS: Yeah! I will also say the title, at least for me, when I saw it was very intriguing—very like, “Oh, what does this mean?” Would you say that you also try to intrigue the reader a little bit with your title as well?

BF: For sure, yeah! You know, that’s what, I guess, what I meant by bringing them to a space of contemplation, of being—of wondering, of curiosity. Like “What’s behind this?”

BS: I would say you definitely did that with this poem. It’s very much like, “Oh, I wonder what that means,” like what the poem is going to be about. So, for our third question: what is the meaning behind the poem’s narrow form—to you?

BF: Yeah… I was thinking about this question, and, of course, I thought about all of them. But this one in particular I was thinking about as a question where thinking about it—after the fact—actually I think is more clear than how I was thinking about it in the moment of writing. And it kind of feels like it was a subconscious thing to make it this structure. I mean I did it on purpose, but I wasn’t necessarily thinking of the reasons that I’m thinking of now.

And the reasons that I think of are that I think it mirrors the kitchen, the tight space that it’s talking about. I’m a young adult, but I have lived in nothing but houses with small kitchens or apartments with small kitchens, so that’s kind of the feeling of this setting. But also what it’s talking about in the sort of—the slippery slope between reminiscing and then dwelling, and the kind of tight space that dwelling on somebody who has passed can bring you in emotionally and mentally. It’s a very constricted mental/emotional state. And I think it reflects both of those things.

BS: For sure. For me, I feel like the form works—I think you did a good job choosing that. And then, for our fourth question: do you think that art can or cannot be—or should or should not be—political?

BF: I have had mentors—people, poets—I’ve heard them say that all art is, in some way, inevitably political. And I don’t know that I think that that’s true. To be honest, I’m not 100% sure what I think about this. But I think that it can and cannot. And which is related to my answer to the should, which is that I don’t think it’s my place to judge whether or not someone should be political with their work. If they decide to… Because it’s your own creative space. And if in your own creativity, it manifests as political or as some people might call political—or the intention is political… Then more power to you.

If your creative space is something that, you know, isn’t—and that’s hard to define, but I do think that they exist—then also power to you. I think they can both happen.

BS: Yeah, and then just for you—would you say that the majority of your pieces are—I’m just curious, I guess—about how you would define most of your pieces or your work.

BF: I mean, most of my work—I don’t know that most of my work falls into any certain category—but I definitely have two major things happening, one of which is definitely political. And it’s thinking about the socio-political state of the world, the United States—so it’s explicitly political. And then, another body of work that kind of explores the space of family and emotion and what’s there, which is hard for me to say is political. I don’t know if I would call it that.

BS: I think that’s a great answer! So thank you. And then for our fifth question: how do you know when a poem is complete—or is it ever complete?

BF: This is something that I’ve thought about also. I can ask myself—or anyone—can ask themselves a couple of questions. Have I surprised myself? Have I said something that I have never experienced before? Either reading or in my own writing. Which, that alone doesn’t mean that you’re done. But if it’s not there, then maybe that’s a good indicator to keep digging.

And then, I was thinking about this in terms of fullness and comfort. Of course, [I] read it over many times and give it space between readings, but… Upon repeated readings, does it feel full? Does it feel like it’s asking for more? There’s something, you know—there’s a vacant space. Or does it feel nice and bulbous and full?

And then comfort—it may feel full, but the things within that fullness… Do they want to be in there? Are they comfortable there? Or does something not want to be there? And then, if you pull it out, that affects the fullness again. I think those are two criteria to think about.

BS: That’s a great answer! Something really actionable—something people can look at… And I assume something you use sometimes for your own work. And then, for question six, we have—what is your process for discovering literary journals to submit to? Do you have a system for keeping track of your submissions or deciding where is best to put your piece?

BF: The simpler questions first: my system for keeping track is Submittable basically. I’m on there, and I can keep a handle on that. Deciding where to submit to is a matter of reading, which is a thread through the next couple of questions—is reading. But super crucial, and that’s also my process for discovering journals—is reading. Reading until I find someone—or a poem that I’m blown away by. And then I go down and read the bio—okay, where else are they published? And then go there and then read. And see who else is there, and do the same thing. It just becomes a rabbit hole of finding great writing.

And I built a database—a whole excel database of hundreds of journals. It’s plotted out like—what do they accept? Is it flash, fiction, poetry? Their submission dates and all of that. It’s a work in progress, but it’s what I use.

BS: Awesome! I feel like excel spreadsheets, you know? Gotta use them. And then for question seven—what do you wish you had known before starting out as a writer?

BF: This was an interesting question to me because of the wording—“started out” as a writer. Because it makes it feel intentional, which I don’t feel is true in my case. I feel like I had an affinity for it for a long time—like in college. And even before that, musically, creatively fiction—and then set it aside because of career and stuff like that. And then [I] came back to it. And then it really took off. So I didn’t really “start out” in the way I perceive this.

But something that I learned early on that was helpful—and I think would be helpful to people who are thinking of spending their time being writers—again, comes back to reading. It’s profoundly helpful to just read and see, expose yourself to all of the different ways creative people out there are expressing themselves and doing it in ways that you never thought about. And then that is inspiration for you to do something in a way you’ve never thought about. So for me, and I know for many people, reading is a super inspirational tool. I think I’d say that.

BS: Awesome! Would you say currently—and I know this isn’t part of the question—do you usually lean toward reading poetry or do you like to read all kinds of things?

BF: I like to read all kinds of things—poetry, short stories, novels, non-fiction… I really enjoy all kinds of things. And you can get different kinds of inspiration from different kinds of things. But I think, related to the next question about writer’s block—is inspiration and stuff like that. When I’m in a space of writing, or when I’m looking for inspiration, then I will intentionally read poetry, because that’s what I’m looking for.

BS: Awesome. Yeah—so going on to that next question. Do you believe in writer’s block? And if yes, how do you deal with it?

BF: Yeah. I feel like my creative space or productivity or whatever has been in a little bit of a slump over the past… Well, maybe for a few months, from maybe August, September, October, there was a lot going on, and that can affect things. Whatever the reason is that you get into creative slumps. And then you sit down, and it’s not as much as coming out as what you may be used to. So that definitely happens, because I’ve experienced it, you know?

I think, for me, what worked—reading, like I was saying. And that’s the big one—I’ve realized. I have not been reading, and I get so much… The “wow” factor that you get from poems—from reading—is a really powerful thing. And I think if you’re a creative, you—or, maybe I should say… Many creatives feed off of that “wow” energy and what to do that, then. And turn around and figure out a way to do that. And that can be a way to access that energy.

Maybe switching up routine… Something I realized was—you know, simple—and maybe it’s simple things. Something I realized—because I’m a morning writer—is I was waking up and trying to write first thing and then walk the dog later. But I realized that if I wake up first and then go walk her, take her thirty minutes outside and wake up a little bit and come back, I’m in a better space. I have more energy. It’s important to also pay attention to yourself and how you’re working and how you’re feeling—your energy levels. And make little changes, if you can.

BS: I think that’s super valuable advice—thank you for that. And then this is our final set of questions. Do you consider yourself an artist? And did you answer change overtime?

BF: I think I do consider myself an artist. And I think my answer… Thinking back, I think I was an artist at different times in my life. There was a time when I was an artist doing this kind of thing, and there was a time when I wasn’t in a creative space. And maybe at that time I wasn’t an artist, and now I am. I think it can fluctuate—it’s a flexible, fluid state of being.

BS: Alright! Well, thank you so much. If there’s anything else you think you would want anyone to know about this piece or about your pieces in general?

BF: I don’t know that there’s anything else I would want people to know about it. Just—when it comes out, read it and experience it. Let it bring you to the space that it brings you to. And I’m grateful for that.

BS: We are super grateful that you submitted to Superstition Review, and congratulations on getting it published in Nimrod Journal! That’s so exciting, and it definitely deserved it. I read it, and I was very much “wow”ed, I guess you could say. The “wow” factor—I very much liked it. And I know that the creative writing students in Amsterdam also really enjoyed it. And I’m sure they’re super appreciative of this interview and getting to know your process a little bit. So thank you so much!

BF: It’s been a pleasure! Thank you—to you and the students.