Many would argue that poems do not matter in today’s world. Very few people read poems voluntarily, and even fewer buy books of poems. Probably 99.9% of poets can’t exist on writing poems; they must work at something or leech off others–parents, spouses, social services. Most people see no practical value in these short, broken lines on the page.

Yet it’s interesting to me that we turn to poetry at crucial times. For example, when we’re in love, suddenly the words, sentiments, emotions found in love poems matter to us. After 9-11, people wrote and read poems because poems often capture what we can’t express. At a recent funeral, three of the five people giving testimonies read poems. In these moments of deep feeling, we often turn to poetry, trying to capture some human essence in words and images.

I am a believer in poetry. Not just because I write poetry but because I read it. Through poems, I have been awakened, I have experienced, and I have imagined worlds that would never have been within my scope of knowledge. I am caught up in the idea that by putting little ink marks on paper, a writer can move a reader to tears, to joy, to feeling, to understanding, all by cobbling together words and images in a particular order.

Poetry matters because poems focus our attention. This modern life is busy and complex. We run and hurry from one obligation to another, often confused by the idea that the busier we are, the more we live. The opposite is probably true. As we rush from project to person to responsibility, we ignore the here and now, the clouds forming in the sky, the heron flying overhead, the kids jumping in leaf piles. Sometimes we ignore the fact that the world is falling apart around us—climate change, world hunger, ethnic cleansing—to name just a few, and poems can urge us to take action. Poems can focus our attention on what we need to do to survive in this world.

Poems require us to stop, slow down, narrow our view on the particular, the specific. Poems may even require multiple readings. This focus hones our ability to perceive and pay attention in our own lives. James Tate, Pulitzer prize winner in poetry, touches on this ability of poetry to capture life’s essence: “While most prose is a kind of continuous chatter, describing, naming, explaining, poetry speaks against an essential backdrop of silence. It is almost reluctant to speak at all…there is a prayerful haunted silence between words, between phrases, between images, ideas, and lines. The reader, perhaps without knowing it, instinctively desires to peer between the cracks into the other world.” Tate implies a sacredness, a holiness, here. There is more to the poem than the words. Something exists between the words and phrases, inside the body of writing, that we sense when we read a good poem. Another modern poet, E.A. Robinson, said, “Poetry tells us, through more or less an emotional reaction, something that cannot be said,” highlighting that impossible nature of true art.

Since experience matters, poems matter. In poems (as in stories, novels, and plays), we imaginatively experience the lives of other people. We see the world from different perspectives and viewpoints. We get a chance to live out experiences we might never have in our own lives. Billy Collins, a former poet laureate of the United States, says, “When we read a poem, we enter the consciousness of another. It requires that we loosen some of our fixed notions in order to accommodate another point of view.” In this manner, we broaden our understanding of the world.

Poems inform us that there are other perspectives, viewpoints, emotions. They enlighten us with other people’s take on life, most likely different from ours. These “voices” coming in affect us, expand us, strengthen and weaken us. Most importantly, they force us to re-think our own narrow perspective and re-examine our ideas.

Poems touch each reader uniquely; they make us feel reassured about our humanity and remind us that we are part of the human family. Readers bring their own experiences, past, emotions, even dreams into the understanding of poems. In his Nobel prize speech, Pablo Neruda puts it so eloquently: “All paths lead to the same goal: to convey to others what we are.” Every poem is an attempt to translate human experience, to explain the unexplainable. We all want to connect with others, and poems are exercises in sharing–an image, a thought or idea, a loss, a hope, a memory. The more we share, the more we grow, understand, and are understood. And the more we share, as readers or writers, the larger we become, more compassionate, more humane, more real.

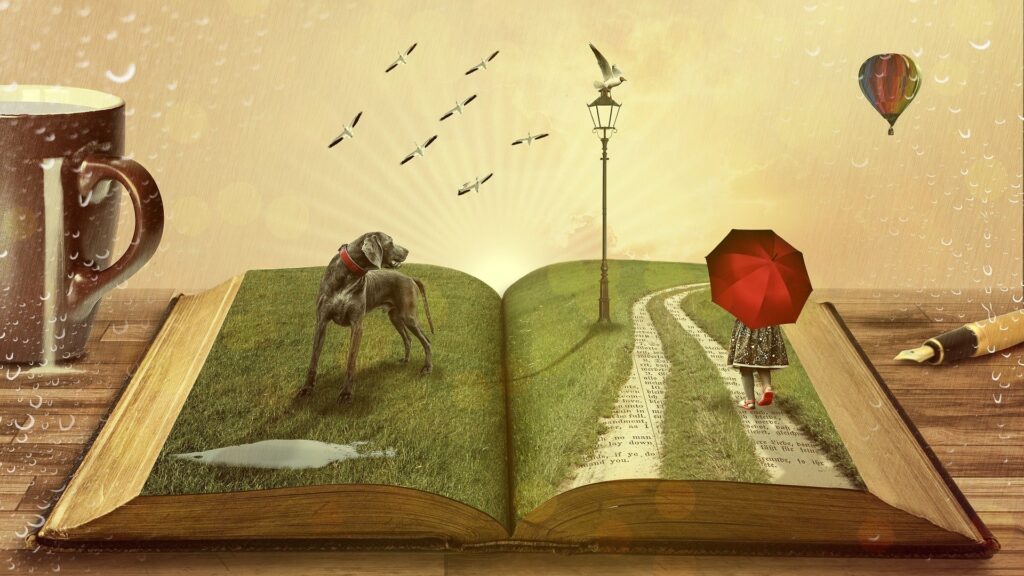

If the imagination matters, then poems matter. Poems stretch our minds beyond their normal limits, and that, of course, builds and strengthens our imaginations. We all know that original inventions and solutions to problems come from people who think creatively, who can imagine worlds beyond the one we live in. Novelist Tom Robbins puts our goal as writers so clearly: “To achieve the marvelous, it is precisely the unthinkable that must be thought.” Writing involves risk-taking. Writing demands the lowering or eliminating of censors inside, and it allows the imagination to play wherever it wants to.

When we read imaginative poems, we exercise our mental muscles; we picture images unknown to us, therefore allowing us to make new and innovative connections that we might not have made previously. Absurd, silly, humorous and surreal poems not only bring pleasure and delight, even confusion at times, but they force us to see and imagine impossible worlds. Combining the impossible with the real nurtures original thought.

Finally, poetry matters because life matters. Gwendolyn Brooks says, “Poetry is life distilled.” All art, in one way or another, shines a spotlight on the here and now, the routine, the miraculous, the mundane, pleading with us to see, to hear, to smell, to feel, to taste the world at our fingertips. Each day is a miracle, and that’s what poems say in that “prayerful haunted silence between words,” as James Tate writes. Every poem I’ve read or written has focused my imagination deeper into life. Each poem adds to the warehouse of my experience.

This is all we have in the end: this precious moment alive. We can plod blindly through each minute and hour and day, living a life of worry and dread and busyness, or we can realize, like poems do, that every experience and feeling, every event and moment, good or bad, conveys the seed of joy and wonder and the miraculous.

Those who live the best are alive the most. And poems help us to live, calling to us like mythical sirens on the ocean of life: Stay awake. Look around. Take the world in. Be alive!