When I was given the opportunity to interview Teague Bohlen about his upcoming talk at ASU I was thrilled—his flash fiction/photography pieces were some of my favorites from Issue 10. His stories are compact and powerful.

When I was given the opportunity to interview Teague Bohlen about his upcoming talk at ASU I was thrilled—his flash fiction/photography pieces were some of my favorites from Issue 10. His stories are compact and powerful.

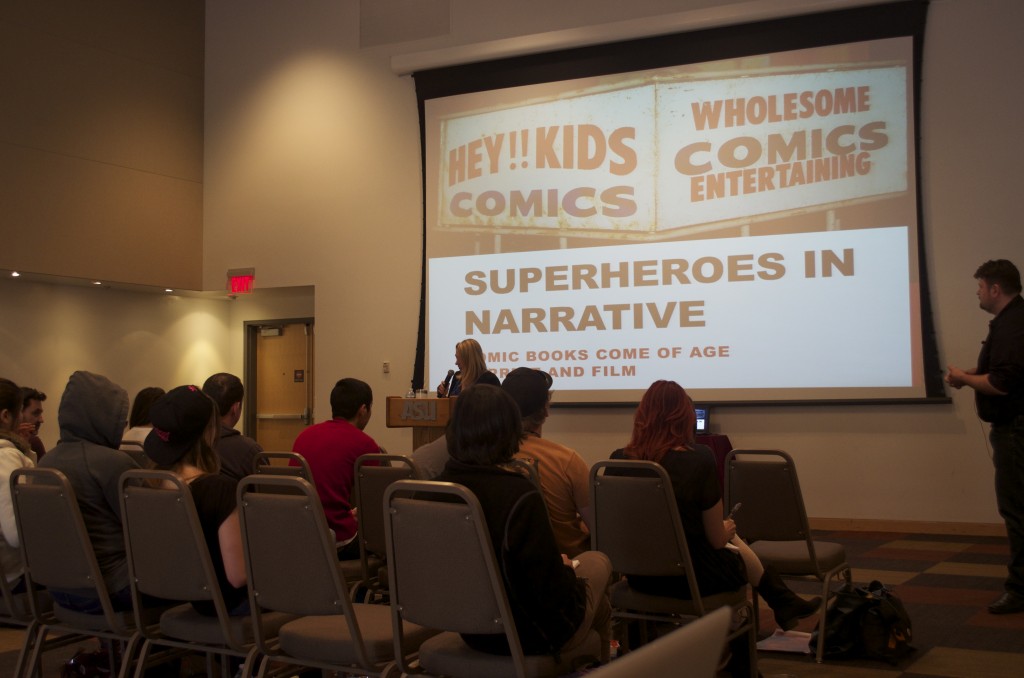

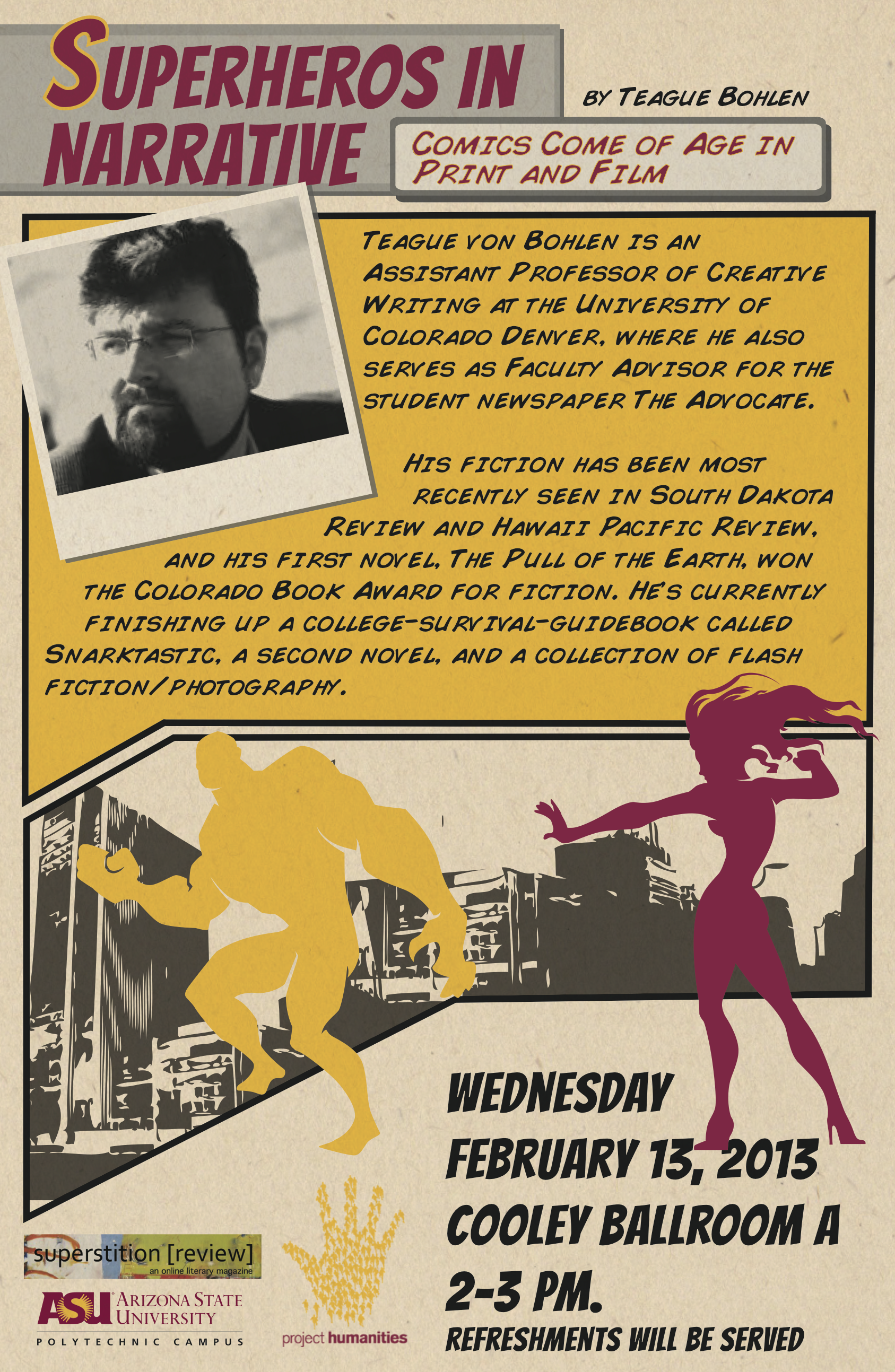

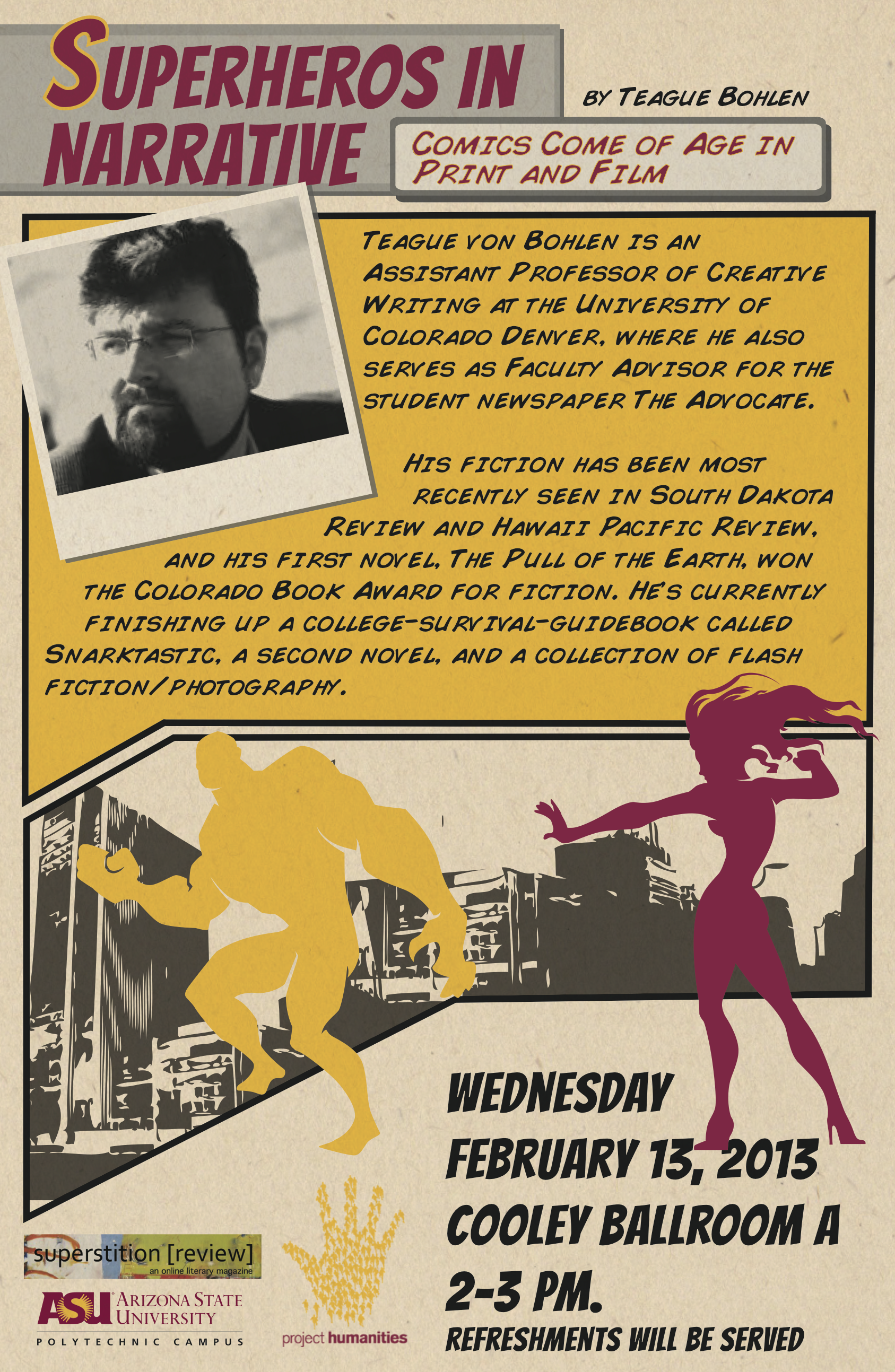

In just a few weeks Teague is scheduled to talk at ASU about a topic of personal expertise—Superheroes. If you enjoy this interview, don’t miss the opportunity to hear Teague speak at the Polytechnic Campus on February 13 from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m.

Brooke Passey: Thank you for taking the time to answer these questions, we are all so excited to hear you speak at ASU in February.

Teague Bohlen: Thank you for having me, both for this interview, and at ASU in February. It’s always good to come back to Tempe, and February is quite possibly the best time of the year to do it. Especially from Colorado.

BP: The title of your talk is “Superheroes in Narrative: Comics Come of Age in Print and Film.” That is intriguing to say the least! Can you tell us a little about where you plan to focus the discussion? Will you talk about the craft of writing with superheroes, the history behind it, the transition to film…? Give us a teaser.

TB: The idea behind the talk is how the archetype of the hero—specifically, in this case, the superhero—has changed over the many years since its modern inception. I’m going to start with a bit of the history of the superhero itself, how it’s changed, and how those changes have been reflected not only in the comics from which those heroes come, but also in traditional literary narrative. It’s an interesting parallel, I think; there’s been a specific maturation of both media over the last few decades–for sure, more for the previously kid-focused comic book medium, but there are certainly parallels. Now that the geeks have inherited the pop-culture earth, so to speak, this is becoming even more apparent, from a book like Chabon’s Kavalier and Clay to a deconstructive film like Whedon’s The Cabin in the Woods.

BP: On your website you mention reading Peanuts comic strips in high school. When did Superhero comics become important to you?

TB: I’ve been reading comic books since I was a young kid. Some of my earliest reading memories were of comic books. My uncle once brought me a huge box of comics when my grandfather passed away—I was five. My grandfather was gone, and my uncle—in some wonderful gesture of love and sorrow and sympathy—brought me a box of comics. There were Archie and Batman and Scrooge McDuck and Spider-Man, the last of whom I already knew from the PBS show The Electric Company, and from his Spidey Super Stories books. A couple of years later, I remember getting hold of the issue of Amazing Spider-Man in which Gwen Stacy—Spidey’s girlfriend—is killed. I remember that blew my mind. They killed someone; someone important. She wasn’t coming back. It was just like real life. I remember it was like a world opened to me—these weren’t just stories where everything worked out (which was true for books like Superman, etc., where the status quo and the cast rarely changed).

BP: This might be slightly off topic but I have to ask you about your upcoming collection of flash fiction/photography. Three of your flash fiction/photography pieces were featured in our last issue (all of which I adored, especially All His Shirts) but what inspired you to combine these two artistic mediums?

TB: I’m glad you enjoyed those. I’ve really come to love flash fiction. I edited for a great journal for a few years—Quick Fiction, now sadly defunct—that really made me appreciate the form. I’d been working in the medium for a while, and a lot of my flash work seemed to be centered around the Illinois Midwest, as was my first novel. It’s where I grew up, and where my heart still very much lies. The idea of adding photography came about when my cousin, Britten Traughber, chose to focus her own artistic bent on the same region. So much of her amazing work is set there, and it seemed like a natural pairing-up. We both wanted to allow the fiction to stand alone, and the photos to stand alone—and to be able to appreciate a new third thing, this alchemy of the two together, when they appear next to each other on the page.

BP: On a similar note, after reading your very serious and compelling stories I was surprised to find out that you were such an expert on comics. How do these two very different styles work together in your life?

TB: For a long time, I wasn’t sure they did! But then I moved from being a TV critic to being more of a pop-culture critic, and then a pop-culture humorist of sorts, and all that’s come together in interesting ways. I have a comic-book novel floating around in my head, which I want to get to at some point–that’s a book about people who like comics, who live in that world and speak that cultural language. People always try to pigeonhole your work into one thing–oh, he’s serious, or oh, he’s funny–but the truth is that most of our best writers are both, and more. Sometimes I spread myself too thin, but I think the range is good. It works for me, anyway.

BP: I read your pieces on Terrian.org and noticed that those photographs were also taken by Britten Traughber, who you just mentioned is your cousin. Did she take all the pictures for your upcoming collection?

TB: She did; the book is very much a collaboration between her and me, and the coming together of our work in rural Illinois. I come from a close family, so I feel like she’s more my sister, really. I’ve always admired her work, and since we share a Midwestern focus in some of each of our work, it seemed like a natural partnership.

BP: And last, but not in the least bit serious, let me end with a question about sugary snacks. I came across an article you wrote in 2009 titled, “The 10 Dumbest Comic Book Hostess Ads.” You made some very pertinent points, but what insights would you add to that article if you had written it after Hostess took their tumble?

TB: Ha! What a good question. You know, just to go back a bit, I love that series of silly lists I did for Village Voice back in the day. I miss doing them. They were crazy fun to research and write up. I’d like to do it again sometime. As for how that particular piece would have changed today, given the apparent demise of Hostess and all its wonderful products…well, honestly, the whole disappearance of Ho-Hos and Fruit Pies has me too depressed to even think about it. Though maybe I should write up something about where Hostess mascots Twinkie the Kid and Fruit Pie the Magician ended up–I’m thinking a lounge act on some ’70s-throwback cruise line.

BP: Thank you so much for your time. It has been a pleasure and we look forward to hearing from you again very soon.

TB: Thank you for the questions, Brooke! Looking forward to coming to ASU and talking comics. We’ll nerd-out, academic-style.