I’ve always been a reader. I don’t know if this is my parents’ fault or not. Recently I found a crayon drawing and questionnaire book I made when I was in elementary school. On one of the pages it asks what my parents do during the day while I’m at school. My answers were: My Dad builds Rockets. My Mom sits on the couch all day and reads love stories. I don’t think that was entirely true, I mean, my Dad read books too. In any case, I do remember that prior to puberty, trips to the mall were exciting for two reasons: first, because I could climb up and sit in the conversion vans in the car dealership that was actually in our mall; and second, we got to go to Walden Books. My family didn’t have a lot of money, so we didn’t buy a lot of new books there, but it was a thrill just to be there and look around. I knew that eventually the books on those shelves would find their way to our city library.

I’ve always been a reader. I don’t know if this is my parents’ fault or not. Recently I found a crayon drawing and questionnaire book I made when I was in elementary school. On one of the pages it asks what my parents do during the day while I’m at school. My answers were: My Dad builds Rockets. My Mom sits on the couch all day and reads love stories. I don’t think that was entirely true, I mean, my Dad read books too. In any case, I do remember that prior to puberty, trips to the mall were exciting for two reasons: first, because I could climb up and sit in the conversion vans in the car dealership that was actually in our mall; and second, we got to go to Walden Books. My family didn’t have a lot of money, so we didn’t buy a lot of new books there, but it was a thrill just to be there and look around. I knew that eventually the books on those shelves would find their way to our city library.

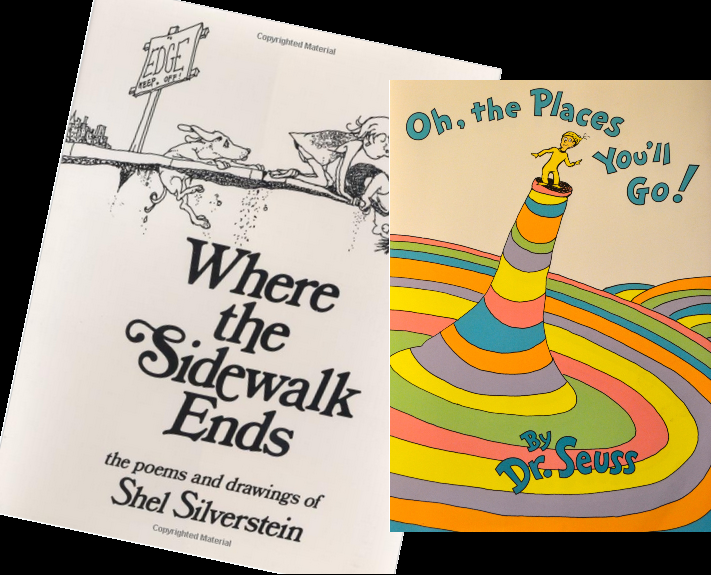

As a kid, I was fairly well read. Once I got beyond Dr. Seuss, I enjoyed Roald Dahl, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Scott O’Dell, Louisa May Alcott, Franklin Dixon, Carolyn Keene, the Choose Your Own Adventure Series, and of course, Judy Blume. There are a few in that list some might consider literary, but many fall into the category of good old genre fiction. I still have many of them because I saved them for my children. And now I’m saving them for my grandchildren, because I don’t think I was as successful as my parents were at passing down the love of literature.

As I got older, I dove harder into genre writing. Once I could get books from the library that didn’t have the purple dot on them, my literary world was blown wide open. I devoured everything from Jean Auel, Piers Anthony, and Marion Zimmer Bradley to Stephen King, Dean Koontz, and Anne Rice. Some of these authors I still read today. Because they’re good, and because I can get lost in the worlds they bring to my mind’s eye.

Once I started my degree program, my literary world was blown open again. Even with all of the reading in my youth, there was much that I missed. Memoirs? Whatever were those? Well, all of those English Lit classes filled me in, and filled me up to the brim with writing on every social topic I could imagine, and a few more besides.

Writing classes and workshops introduced me to the short story, and the idea that writers who don’t get paid are somehow of more value than those who do. I’m not much for martyrs, but I bought in. In my few years in school, my professors helped nurture in me a love of the short story, and an appreciation for the craft of drawing them out of myself and others. And so now, my private library grows full of chapbooks and short story collections. To my list of favorite authors I’m adding Roxane Gay, Aimee Bender, Stacey Richter, Matt Bell, Dan Chaon, Tara Ison, Margaret Atwood, and so many more.

But for all my education, and my editorship with a literary magazine, and my degree in English and Creative Writing… I still read Anne Rice. In fact, she might just be my very favorite person ever (not that I know her personally, but I do follow her on Facebook, so I feel like that counts… anyway).

I’m reminded of this funny thing that happened recently.

My husband and I raised our children in a suburban neighborhood of the sprawling Phoenix Metropolitan Area. We had a modest income, and a modest house. We drove practical cars, and our kids went to public schools. There was a house of worship a half mile in any direction from our house. Our neighbors were diverse. To the east was a family of folks who spoke little English, had obnoxious barking dogs, and always had parties in the front yard instead of the back. To the south were the drug dealers. The husband rode a very noisy Harley and cut his entire lawn holding a Weedwacker in one hand and a beer in the other. His wife had no teeth and only wore a bra on Sundays. (I guess they weren’t very good drug dealers.)

My husband and I raised our children in a suburban neighborhood of the sprawling Phoenix Metropolitan Area. We had a modest income, and a modest house. We drove practical cars, and our kids went to public schools. There was a house of worship a half mile in any direction from our house. Our neighbors were diverse. To the east was a family of folks who spoke little English, had obnoxious barking dogs, and always had parties in the front yard instead of the back. To the south were the drug dealers. The husband rode a very noisy Harley and cut his entire lawn holding a Weedwacker in one hand and a beer in the other. His wife had no teeth and only wore a bra on Sundays. (I guess they weren’t very good drug dealers.)

We lived in that house 15 years, and our kids came up just fine.

And just a couple of months ago, we moved. Since our income has doubled, so has our mortgage and the square footage of our new house. Our new block is glorious. The neighbors all cut their grass on Wednesdays, and everyone drives a new car. There are bunnies and quail everywhere, and no one parks in their lawn.

School just started a couple weeks ago, and as I was driving past the elementary school on my way back from my morning Starbucks run, I noted that the crossing guard drives a Jaguar. A Jaguar.

This is it, I thought, we have definitely arrived. All of that hard work, education, ladder climbing, etc., has all paid off. Finally. Now we can live among the educated folk. People like us. Cultured people. People who read. If the people across the street are drug dealers, well they’re damn good ones because their kids drive BMWs.

And then I turned down our street. It was a Thursday. Blue barrel pick up day. About three houses in, out came a neighbor down his drive way, pushing his barrel out to the curb. He was wearing a pair of very snug fitting, bright red boxer briefs. His hairy belly was spilling over the waistband, and his tangled bedhead hair pointed in all directions from his unshaven face. He looked up as I drove past. Smiled.

I about choked on my chai.

But it’s okay. I’m glad I saw him. It’s a great reminder: there’s room on the block for everyone. He cuts his grass, he parks in the garage. Maybe his wife builds rockets.