“I can’t fathom writers married to writers and musicians married to musicians. There’s your enemy in bed beside you.” —T.C. Boyle

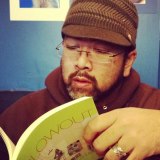

There isn’t a good history of writer couples. Think of the Fitzgeralds. Think of Plath and Hughes. But here I am—knock on wood—married to the poet Katherine Riegel for the past 11 years. I can say, without doubt, that our relationship has shaped me as a writer. If we had never met in Carbondale, IL, those many years ago, I might be teaching high school somewhere, or back in Chicago working at a camera store. Katie is my creativity fuel, my muse, my motivation. I can also say, with certainty, that without me, Katie would still be a poet.

2.

Recent email to Publisher/Friend

Dear ____________,

You may know by now that Katie has gotten her second book of poetry accepted for publication. But you don’t know how much we are in fierce competition with each other, and how I need to have my second book come out at the same time. That said, would you guys be interested in taking a look at my essay collection, Southside Buddhist?

By the way, I’m kidding. Only a little. But seriously, you interested?

Sincerely,

Ira “Bad Husband” Sukrungruang

P.S. She can’t win!

3.

We have learned how to be with each other. We know that I prefer the left side of the bed. We know that she hates June bugs. We know that I hate spiders. We know that she has to figure out tips on checks at restaurants. We know that I will have to cook most meals. We’ve also learned what to say about each other’s work. This took years. We are both stubborn in our own ways, and believe, most of the time, that we are right. Katie is more outwardly stubborn. I’m more inwardly stubborn. She voices her displeasure. “You’re wrong,” she’ll say. I keep it inside. “You’re wrong,” I’ll say on the inside.

Now we have a system. It’s really not a system. We tell each other our work is the best on this planet. No other writers rival our brilliance. And together, we are like those Japanese animes where we can join and become an ultimate power.

“Wonder Twin Powers! Activate!”

4.

We’ve come to know other writing couples: Jon and Allison, Chad and Jennifer, Jeff and Margot, Stacy and Adrian, Aimee and Dustin, Michael and Catherine. Sometimes we go on writing couple dates where most of the time we talk about TV. Writers love TV. TV and food.

We are known as Katie and Ira, a two-headed writing beast. She is the phoenix, and I am the dragon. At readings or conferences, if we are not together, people will say, “Where is __________________?” This happens a lot to writing couples. One of our friends once said, “We’re taking a break,” and this caused such a stir that soon the writing world was abuzz. “Did you hear? So and so are breaking up!” It was the best joke ever, she said.

When we appear by ourselves, it is to others as if we are suddenly without a limb.

5.

In “Enduring Discovery: Marriage, Parenthood, and Poetry,” Brenda Shaughnessy and Craig Morgan Teicher write: “We root for each other’s work, which is good because these books delve into our shared private lives.”

I write about Katie often because I write about what it means to belong to two cultures—Thai and American. Katie, however, very seldom writes about me. When we were first dating, I’d say, “Write a poem about me.” I’d say, “You must not love me because I’m never in your work. I love you because you’re always in my work.” She’d shake her head. “Listen, if I begin writing about you, that means our relationship is not doing well. I only write about bad relationships.” This is true.

Eleven years later, still nothing written about me.

This is a blessing.