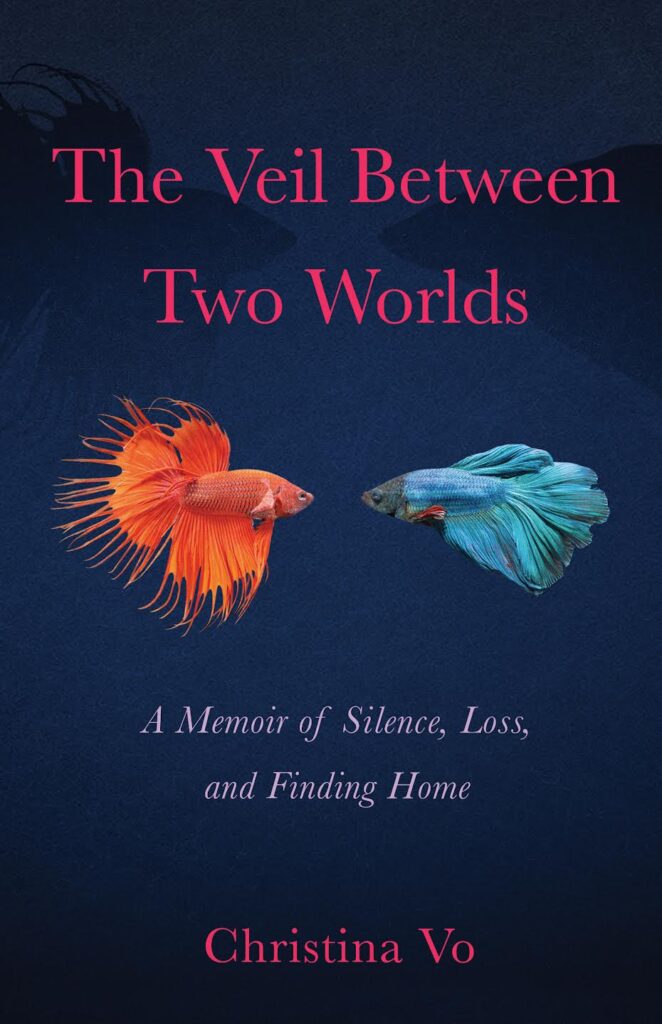

Coming in April 2023, The Veil Between Two Worlds, published by She Writes Press, is Christina Vo’s debut book and memoir. With a matter-of-fact and poignant voice, Vo lets readers peak behind the words to glimpse her life. With the loss of her mother at a young age—and a distant father—Vo details time spent trying to heal and find a place she can call home. She draws readers in with her keen descriptions of what “home” is or can be—both as a physical space and an emotional/spiritual one. Vo writes that home is “a place we find within ourselves—warm, comforting, and nurturing.”

The memoir itself recounts Vo’s journey with one of her closest friends—David—as they go on a roadtrip together from San Fransisco to Santa Fe. While they travel, Vo thinks back on her life and what has led her to this point. Ultimately, Vo’s memoir is a deep, hopeful contemplation on how lives intertwine.

Christina Vo is a Vietnamese-American writer. She has worked for international organizations, including UNICEF and the World Economic Forum, in Vietnam and Switzerland, respectively. She also owned and operated a floral design business in San Francisco. She has degrees from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the London School of Economics and Political Science. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. To learn more about her and keep up-to-date on her latest works, visit her website.

To preorder The Veil Between Two Worlds, go here.

We’re also very excited to share an interview that dives deeper into Christina Vo’s memoir. This interview was conducted via email by our Blog Editor, Brennie Shoup.

Brennie Shoup: You’ve done a lot of traveling, and you’ve lived in a number of countries, including the USA, Switzerland, and Vietnam. How have these experiences contributed to your writing? How do you see your writing in a global context?

Christina Vo: Yes, absolutely—I believe that our sense of place, where we’ve lived, the people we’ve met, and where we call home (can be multiple places actually) have an impact on who we are and who we become. I lived in Vietnam on three separate occasions in my twenties, and as I mention when I speak about a forthcoming project related to Vietnam, living there shaped my adult identity. I didn’t graduate from college and move to a city like San Francisco or New York; I went to Hanoi. At that age, meeting and working with people from all over the world, made me realize—there’s no ONE right way to live one’s life, and I think that ultimately shaped how I thought about my whole life and career—that it didn’t have to be linear. It didn’t have to look like anyone else’s. So yes, my perspective and my writing is inevitably shaped by my travels; however, I think the theme of place really comes in more with my second book.

In regards to how I see my writing in a global context, I remember a friend of mine, who is a Vietnamese writer, told me that if I started off with the Vietnam story, I might be pigeonholed as a writer who can only write about Vietnam. Of course, I don’t entirely believe that’s true; I feel as artists, writers and creators, as we continue to live, we will evolve. However, those words did stick with me. I specifically see The Veil as a story mainly for women who are navigating their paths, so that’s how I connect it to a global context, even though obviously, depending on where a woman is living in the world, she will face different challenges.

But at heart, we all, whether consciously or not, go through the life questions: Why am I here? Why do I hold these wounds? What is stopping me from living my full expression of myself? How do I define myself, beyond the societal expectations of who I should be? And, how do I express the fullest version of myself? Essentially, I see that these questions, which drive this first body of work, are universal to some extent.

BS: You mention creativity and expression in your memoir. When did you know that you wanted to write as a part of your creativity? Have you ever experimented with other art forms, such as drawing or painting?

CV: I believe creativity and expression is fundamental to who we are as human beings navigating this earthly world. In large part, I would classify The Veil as a spiritual memoir, so I feel that it’s natural that creativity and expression come up and through the book as a theme.

I have always been drawn to writing but never really claimed it until the pandemic, and until I really sat down to finish this memoir. Writing has always called to me, even when I was a teenager and facing the death of my mother. I remember something within me saying, “Write this now. So that you can remember it.” Of course, I didn’t, but the things that are truest in your life will always find a way back in your life. And what I’ve learned is that you have to claim them or there will be this quiet dissatisfaction which might eventually consume you.

I have dabbled in other forms of creativity, from trying to create a sustainable handbag line while living in Vietnam and also working with local craftspeople in developing countries to bring their wares to market. I also often worked on small projects helping with interior decorating throughout my career, and of course, started blogs that I also stopped after some time. In my mid-thirties, I ran a flower design business. I was pretty much self-taught, but working with flowers was a huge part of my creative life and healing (and another long topic entirely). It was beautiful—and incredibly challenging—to work with flowers on a regular basis. It taught me a lot about the natural process of life and the powerful lessons of Mother Nature herself.

BS: The Veil Between Two Worlds deals a lot with loneliness vs. connectedness. Did you notice whether any of your topics influenced the form or shape of the book itself? If so, how?

CV: Thank you for mentioning that and for picking up on that theme of loneliness vs. connectedness. That’s actually probably one of my lifelong dilemmas that I came to this planet to grapple with. Bear in mind that The Veil was written during the pandemic, so I also believe the external factors of all of our lives (and the inevitable loneliness of social distance) was pervasive through the writing process.

I had wonderful developmental editing support for this book and also benefited from a six month memoir writing class I took during this time. When I started I didn’t really know what it was about, I didn’t know the arc, and while the book covers a period of my own life between 40-42, a time of deep spiritual transformation, I didn’t want to tell the story chronologically, so it weaves in and out of that period of time and also has a heavy backstory with the interactions with my family.

So, yes, I think that topics did inform the shape, as when we’re experiencing something in the moment, it’s also inevitably related to something else in the past. For example, let’s say we’re facing an ending or a break-up of some sort, we will feel the pain of that experience but it might also trigger something that happened in the past, even a childhood experience. I do believe that is probably what unintentionally shaped the way this story is told—the moving between time, and as referenced in the title, between worlds.

BS: Do you have any other pieces you’re working on?

CV: Yes, I’m working on two larger bodies of work—both of which I’m really excited about. One is what I call an intergenerational memoir, which I’m collaborating with my father on. It’s about our very different relationships with Vietnam. For him, leaving the country he loved and lost at the end of the war, and for me, Vietnam was really where I became an adult in my twenties, having lived there on three different occasions. I feel it’s a beautiful book because it touches on universal themes—intergenerational trauma, father-daughter relationships, immigration and reverse migration.

The second body of work is similar to the first memoir loosely based on my life, but I suppose it would be classified as auto-fiction or a semi-autobiographical novel. I’m really excited about this one because it focuses more on being a woman in the world today and grappling with identity, balancing the masculine/feminine within, and very similar to my own character—being a woman that’s not shaped by society (even though to some extent we all are) but by that I mean, not living based on other people’s expectations on how we should live.

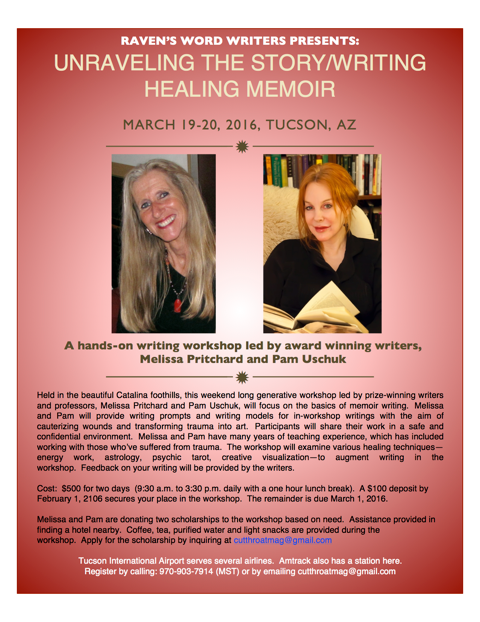

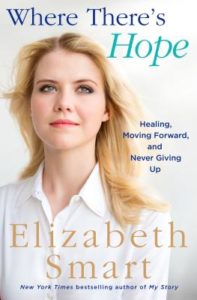

Author and activist Elizabeth Smart—who first gained national attention at age fourteen when she was kidnapped from her home by religious fanatic Brian David Mitchell and his wife Wanda Barzee—will be at Changing Hands Tempe (6428 S McClintock Dr, Tempe, AZ 85283) on Thursday, March 29 with her new book

Author and activist Elizabeth Smart—who first gained national attention at age fourteen when she was kidnapped from her home by religious fanatic Brian David Mitchell and his wife Wanda Barzee—will be at Changing Hands Tempe (6428 S McClintock Dr, Tempe, AZ 85283) on Thursday, March 29 with her new book