Went to a cousin’s wedding a few weeks ago, it was nice, flowers, love, family, food, drinks, you know – nice. Well not all of it, that’s more of a cover, thing someone said in the cab on the way home because parts of it were, mmmm, not so nice. The vows, oh my god over the top and the dresses, I know the bride’s supposed to steal the show but come on, peach for your maids, looked like they all went shopping at the same week after junior prom yard sale. And then there was uncle Jean’s toast, roast, I mean toast. You know what I mean, you’ve been to a wedding with an open bar six months after someone got divorced before too right? Of course you have, well this is going to be a little like that, rough in places, but remember – free bar, so hang in there.

Went to a cousin’s wedding a few weeks ago, it was nice, flowers, love, family, food, drinks, you know – nice. Well not all of it, that’s more of a cover, thing someone said in the cab on the way home because parts of it were, mmmm, not so nice. The vows, oh my god over the top and the dresses, I know the bride’s supposed to steal the show but come on, peach for your maids, looked like they all went shopping at the same week after junior prom yard sale. And then there was uncle Jean’s toast, roast, I mean toast. You know what I mean, you’ve been to a wedding with an open bar six months after someone got divorced before too right? Of course you have, well this is going to be a little like that, rough in places, but remember – free bar, so hang in there.

Gubul gubul, love that word, just the way it feels coming out of my mouth, try it … gubul gubul. Nice right? No you didn’t just say something naughty, but naughty of you to have thought you did. Means curly, in Korean. You had a feeling it did, didn’t you, just the way it sounds, I mean it sounds curly. Yes that’s a long winded way to introduce onomatopoeia, but that’s where we start this; the sound of a word mimicking its meaning – sound having meaning. However, words have other sounds in them too, we say them after all. They got their syllables, get them from their phonemes, morphemes and the like, those things we all stress through pretty much the same way. So yeah, sounds have meaning.

Almost ‘sounds’ like music, I mean, we’ve all heard this one right – music is a language, tickles some universal primitive reptilian leftover nub on our brain stems. Well it’s a can of worms I’ll keep my pinkie out of for now. No, well yes, but not all the way out, just let me dip in and get at the part about music being a sound that can express emotion. Express, convey, prompt – I can’t nail it down with one word. So you pick the one that works on you – just make it mean the way a particular piece of music can make you feel happy, or sad, or scared, or whatever, but pick a word that means that for you. Because the sounds of music can do that.

So here we are, a few premises deep, words are sounds that have meaning and the sounds of music can get at emotions. Sounds doing things, sending out information we can get things from. Okay, so far so good, and excuse the pedant in me but uncle Jean assumed he had us in the palm of his hand too and its right here that I need you with me. So let’s close up the bar for a few minutes and focus. Now, what if those strings of sound our words make are sending out the same kind of emotional meanings music does?

No, no, no, sit back down here, I’m serious. Okay, for sure the sounds that music produce are much more complex than those available to words. Music has tempo, mode, loudness, melody and rhythm, while words on the other hand only have access to tempo and rhythm. But don’t let that get you down, a lot can be done with tempo and rhythm. Let’s start with tempo or speed. Quick gets you happiness, excitement or anger, whereas if you slow it down it slips over to sadness or serenity. Mixed bag? I know, but all is not lost just yet because we still got rhythm. You get the rhythm smooth and consistent and it’ll spell happiness again. Easy enough way to double down on it, quick and smooth musics out happiness. However, if the rhythm was roughed up but you still kept the speed up then you’d get something closer to uneasiness.

Just think about this for a minute, the sounds of words being subvocalized in a reader’s head as they make their way through a paragraph, about say betrayal, wouldn’t it be something if the actual tempo and rhythm of their inner voice was producing a meaning synchronous to the combined lexical meaning of the words. Wow, you’re damn right wow, it would be devilish, the reader would have no idea it was happening, they’d just feel it, same way they feel emotions from music.

However, as with most things, the rub lives in the how. Tempo, speed, you can fiddle with that. Sure individual reading speeds will vary, enter a thousand variables you can’t control for and then throw them away. We’re looking big picture here and big picture tempo is in a writer’s hands. Lexical density, vocabulary sophistication and syntactic complexity, three puzzle pieces every single sentence or paragraph will have lurking inside of them. Ramp them up and the reader slows down and vice versa gets you on the flip-side. And its relative right, slow for me is fast for you, who cares, music’s playing in each individual head, this isn’t a concert after all. That’s the hard one, rhythm, or beat, is a much easier pulse to finger. Syllables, those things you used to count out on your digits when you were a kid, if that isn’t a rhythm I’ll never dance again. You want to get even finer, add in individual word stresses, that place where your voice rises inside a word. In between the words is another playground: punctuation, comma, slash, dash – a writer almost becomes a Lamaze coach for a reader’s respiration.

Now you might be thinking this is even worse than uncle Jean’s speech, but come on, I’m not saying the meaning being transmitting through subvocalized tempo and rhythm are primary. There’s no way they are going to make your love story come out horror show. Not at all, because if I’m right here, then this music is already inside everything you’ve ever written. What I’m thinking is, this ability of music to transmit emotional meaning can be used to supplement the lexical meaning of a sentence or paragraph. Or perhaps a passage could be written with opposite meanings, one where the lexical and the musical were polar to add a touch of doubt to the lexical, like an unreliable narrator.

There’s no need to work through all the different ways this can be kajiggered. If you think this is as bad as uncle Jean’s toast no worries, I’ll go sit in the back with him and watch the bride and groom dance to a love poem put to slow paced (serenity), smooth patterned (happiness) piece of music. But if you hear it too, you know where we are.

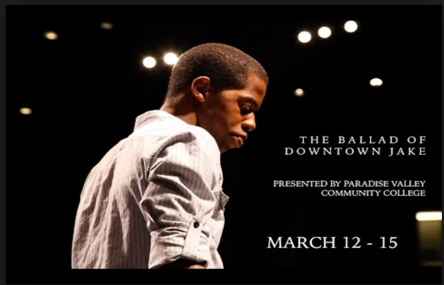

Today we are pleased to feature poet Ephraim Scott Sommers as our Authors Talk series contributor. In this brief interview, Ephraim discusses his life as a poet and as a singer/songwriter, and how each endeavor creatively informs the other.

Today we are pleased to feature poet Ephraim Scott Sommers as our Authors Talk series contributor. In this brief interview, Ephraim discusses his life as a poet and as a singer/songwriter, and how each endeavor creatively informs the other.

Royse Contemporary is so excited to present “The Sound of Color” by

Royse Contemporary is so excited to present “The Sound of Color” by  Today we are pleased to feature author Steven Faulkner as our Authors Talk series contributor. Steven’s podcast is a unique treat: he has recorded his nonfiction piece from Issue 14 with guitar accompaniment. Steven’s voice blends with the lull of the guitar to create a truly moving work of art. His essay reflects on the life of his youngest child, Alex, as he grows up. Steven begins by describing Alex’s birth and ends when Alex “is 22 years old” and “[h]is father and mother have little influence,” with many anecdotes to fill the time in between.

Today we are pleased to feature author Steven Faulkner as our Authors Talk series contributor. Steven’s podcast is a unique treat: he has recorded his nonfiction piece from Issue 14 with guitar accompaniment. Steven’s voice blends with the lull of the guitar to create a truly moving work of art. His essay reflects on the life of his youngest child, Alex, as he grows up. Steven begins by describing Alex’s birth and ends when Alex “is 22 years old” and “[h]is father and mother have little influence,” with many anecdotes to fill the time in between. Data-saturation as an aesthetic practice emerged from the late 20th-century media practice of working with partitions, fragments, multi-samples, and frames, (exemplified by the commercial advertisement, the audio loop, the film montage, the remix, and so forth). Current advances in editing software have enabled the fragmentation of any digital file to occur down at the levels of the tiniest pixel, frame, or multisample. For Deleuze, the montage was a means of releasing the appearance of linear and sequential time from the movement-image, that is to say that editing imbued film with the illusion of a linear timeline. In terms of audio applications, Karlheinz Stockhausen generated entire soundscapes from singular patterns of electronic pulsations; utilizing these cyclic pulse-patterns as material that could be subsequently transposed to other frequencies of any duration; this action resulted in the creation of singular timbres within his compositions Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte. Today, in our cultural wasteland, which is littered with moving images and audio, a wasteland literally saturated with infinite variegations of data and their technological transformations; this state has enabled the artist to rupture with past forms, conceptions, and materials in the creation of an artwork.

Data-saturation as an aesthetic practice emerged from the late 20th-century media practice of working with partitions, fragments, multi-samples, and frames, (exemplified by the commercial advertisement, the audio loop, the film montage, the remix, and so forth). Current advances in editing software have enabled the fragmentation of any digital file to occur down at the levels of the tiniest pixel, frame, or multisample. For Deleuze, the montage was a means of releasing the appearance of linear and sequential time from the movement-image, that is to say that editing imbued film with the illusion of a linear timeline. In terms of audio applications, Karlheinz Stockhausen generated entire soundscapes from singular patterns of electronic pulsations; utilizing these cyclic pulse-patterns as material that could be subsequently transposed to other frequencies of any duration; this action resulted in the creation of singular timbres within his compositions Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte. Today, in our cultural wasteland, which is littered with moving images and audio, a wasteland literally saturated with infinite variegations of data and their technological transformations; this state has enabled the artist to rupture with past forms, conceptions, and materials in the creation of an artwork.

Every so often, I like to listen to Stephen Sondheim’s thoughts on writing. This isn’t because I want to write musicals. And while some people may herald Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize as the long overdue blurring of songwriting and literature, I’m not one of them. As much as I like Dylan, I don’t believe a songwriter is also a poet. In fact, one reason I seek out Sondheim’s thoughts on language is because lyric writing is different enough from what I do to make his observations feel fresh.

Every so often, I like to listen to Stephen Sondheim’s thoughts on writing. This isn’t because I want to write musicals. And while some people may herald Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize as the long overdue blurring of songwriting and literature, I’m not one of them. As much as I like Dylan, I don’t believe a songwriter is also a poet. In fact, one reason I seek out Sondheim’s thoughts on language is because lyric writing is different enough from what I do to make his observations feel fresh.