NonFiction

Letter Review Prize Launches for July-August

Letter Review has launched their bimonthly Short Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry and Manuscript Prize for July-August. The contest has a total prize pool of $3800, and includes publication for the winners.

In each of the four categories, there are three winners who are published, promoted across social media channels, and split the prize pool.

Letter Review Prize for Short Fiction

Three winners are announced who are published, accompanied by an attractive original commissioned artwork. Winners share in the $1000 total prize pool. Twenty writers are longlisted and ten writers are shortlisted. All entries are considered for publication, and for submission to the Pushcart Prize and other anthologies.

Entry Fee: $20 for one submission, $35 for two submissions ($5 in savings), and $45 to enter three ($15 in savings).

Dates: Open now, closing August 31 11:59 p.m. ET.

Word Length: 0 – 5000 words.

Details: Open to anyone in the world. There are no genre or theme restrictions.

Letter Review Prize for Nonfiction

Three winners are announced who are published, accompanied by an attractive original commissioned artwork. Winners share in the $1000 total prize pool. Twenty writers are longlisted and ten are shortlisted. All entries are considered for publication, and for submission to the Pushcart Prize and other anthologies.

Entry Fee: $20 for one submission, $35 for two submissions ($5 in savings), and $45 to enter three ($15 in savings).

Dates: Open now, closing August 31 11:59 p.m. ET.

Words: 0 – 5000 words.

Details: Open to anyone in the world. All forms of nonfiction are welcomed including: Memoir, journalism, essay (including personal essay), fictocriticism, creative nonfiction, travel, nature, opinion and many other permutations.

Letter Review Prize for Poetry

Three winners are announced who are published, accompanied by an attractive original commissioned artwork. Winners share in the $800 total prize pool. Twenty writers are longlisted and ten are shortlisted. All entries considered for publication, and for submission to the Pushcart Prize and other anthologies.

Entry Fee: $15 to enter one poem, $27 to enter two (save $3), and $35 to enter three (save $10).

Dates: Open now, closing August 31 11:59 p.m. ET.

Lines: 70 lines max per poem.

Details: Open to anyone in the world. There are no style or subject restrictions.

Letter Review Prize for Manuscripts

Three winners are announced who have a brief extract published, receive a letter of recommendation from the judges for publishers, and share in the $1000 total prize pool. Twenty writers are longlisted and ten are shortlisted.

Entry Fee: $25 to enter one submission, $45 to enter two (save $5), and $60 to enter three (save $15).

Dates: Open now, closing August 31 11:59 p.m. ET.

Words: Please submit the first 5000 words of your manuscript, whether it be prose or poetry.

Details: Open to anyone in the world. The entry must not have been traditionally published. All varieties of novels, short story collections, nonfiction and poetry collections are welcomed. Manuscripts which are unpublished, self published, and some which are indie published will be accepted. Review full entry guidelines for further details.

The judges will be Ol James and Kita Das.

All entries are marked blindly to ensure fairness for all writers. All contest entries are considered for publication, and for submission to the Pushcart Prize and other anthologies. Read some previous submissions here.

Entry is open to anyone. To enter, visit https://letterreview.com/information/.

The contest closes August 31 11:59 p.m. ET.

Letter Review is a literary magazine with a mission to publish new work, foster a supportive creative community, and help writers with all matters related to being published, performed and produced. Letter Review promises to pay writers professional rates and seeks submissions from writers across the globe. Letter Review is a proud member of CLMP and adheres to the CLMP Contest Code of Ethics. Letter Review features interviews with professional writers, publishes helpful information, runs competitions with monetary prizes, and remains open to unsolicited submission of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry.

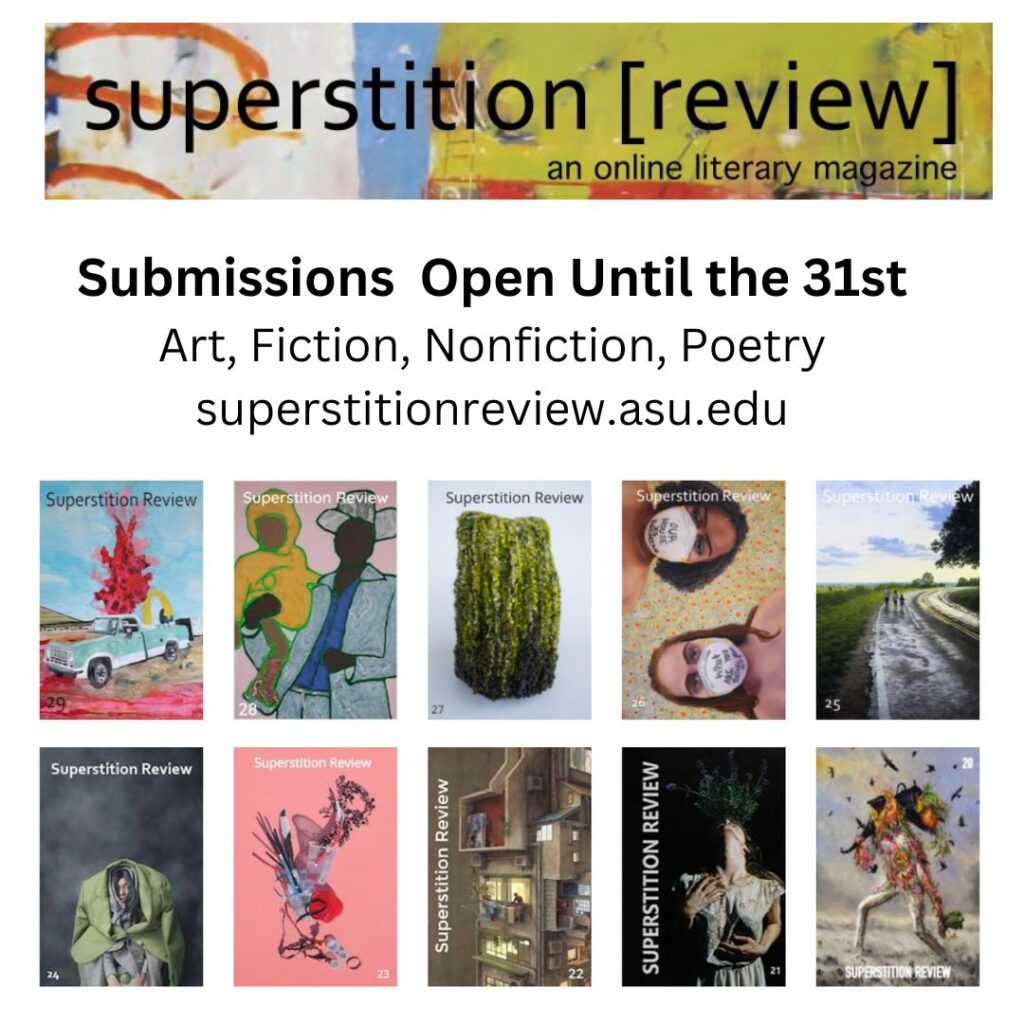

Superstition Review Submissions Open

Superstition Review is open to submissions for Issue 31! Our submission window closes January 31st, 2023.

Our magazine is looking for art, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Read our guidelines and submit here.

Issue 30 Launch Party

Biggie’s Life After Death, a Guest Post by Brian Huba

I was a senior in high school when the Notorious BIG died. Back then, during the height of the East Coast vs. West Coast Rivalry, hip-hop figures felt more like professional wrestlers than young men. They had “stage” names. They had entourages. They operated in a constant state of conflict. Their whole scene was so over the top, it ceased to be real for me. Now it’s 25 years later. I’m 42 years old. I teach English at an inner-city high school in Upstate New York. And I’m still trying to process Biggie’s violent death, to properly lament all that was lost on that tragic night in 1997.

A few days ago, I saw a Facebook post from a woman I grew up with. It read, “SiriusXM channel 105 is now Notorious BIG radio!!!” Without delay, I punched it up, and suddenly I was 17 again. It was Memorial Day Weekend, which meant everyone was at Lake George, a resort town sixty miles north of Albany, and “Mo Money, Mo Problems” blared from tricked-out cars and Jeeps with no doors that crawled down the crowded strip, Federal agents mad ‘cause I’m flagrant/tap my cell and the phone in the basement… Biggie had been dead just two months, and his posthumously-released double-album Life After Death ruled the radio waves. We had no idea who’d shot Biggie. But we understood it was revenge for Tupac Shakur’s slaying the previous November. And now that both kingpins were gone, America’s Rap War could end.

It might seem strange for a white boy from Upstate New York to feel any kind of connection with Biggie Smalls, whose birthplace of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn is practically on another planet. But my life began much like his. I was born September 26th, 1979 at Albany Medical Center. My mother was just twenty years old when she had me. I never knew my real father. Me and mom started out with her parents in a part of North Albany that had once been dominated by an Irish-Catholic constituency. But, by the time I arrived, a racial shift was in full swing. I was the only white kid in my kindergarten class. Like Biggie, I suffered from strabismus, a medical condition in which the eyes don’t properly align. From this, I developed a crippling inferiority complex. I refused to have my picture taken. I wouldn’t make eye contact with people when they spoke to me, often giving the impression that I was hiding something, or lying about something. Then I heard Biggie say, Heartthrob–never/Black and ugly as ever, with all the confidence of a King. And that gave me confidence. That lyric became a mantra. It helped me stop hating myself. Instead of letting my unfortunate eye condition defeat me, I took steps to correct it.

As a teacher, my first classroom was a converted storage area in the school’s basement level. The walls were paint-peeled and pockmarked. There was no window. No bookshelves. No books. I was assigned five sections of remedial English, the ones nobody else wanted to work with. My students were mostly black or Hispanic. They had discipline problems. They came from unthinkable living situations. The average literacy was at a second or third grade level. Before I could actually teach them anything English-related, I had to establish some sort of connection. I tried icebreaker games like “This or That” and “Desert Island.” Nothing worked. They saw me as just another white-guy teacher in their endless line of white-guy teachers. Then everything changed. One day, in early October, two boys at the back table began to loudly argue, and I wasn’t sure what I’d do if they got physical. At some point, one boy said to the other, “You want beef, bring it.” Without thinking, I began to rap, What’s Beef?/Beef is when you need two Gats to go to sleep/Beef is when your moms ain’t safe up in the streets…

“Yo, Huba, you know Big!?”

“Yeah, I know Big.”

I still work at that same school. My current classroom is on the top floor. Its windows overlook a courtyard that doubles as the Senior Lounge in warm weather. I’ve been here for sixteen years. In that time, I’ve taught all the most-recognizable writers, everyone from William Shakespeare to Stephen King, Maya Angelou to Ernest Hemingway, John Grisham to John Steinbeck, Harper Lee to JD Salinger. And I can tell you with total certainty that the Notorious BIG is a finer wordsmith than all of them. Don’t believe me? Google the lyrics to “Everyday Struggle,” then ask yourself: who can write this? Who can so masterfully manipulate the English language? I’ve poured over Biggie’s catalog for two decades and it still scrambles my brain. Every line, every lyric: stratospherically brilliant. As an educator, and a published writer, I wouldn’t have the first clue how to teach someone to do what Biggie could do. All before the age of 24! I can only come up with two conclusions. 1) He read everything under the sun, fully absorbed every word on every page, then instantly understood how to weaponize it. Or, 2) Biggie Smalls was a God.

Sometimes when I start class by saying, “Okay, guys, here’s today’s agenda–” I’ll silently sing to myself, …Got the suitcase up in the Sentra/Go to Room 112/Tell them Blanco sent ya…

The best hip-hop song of all time is Biggie’s aspirational anthem, “Juicy,” which begins with the line, Yeah, this album is dedicated to all the teachers that told me I’d never amount to nothin.’ This sentiment hits me hard. Presumably, if what Biggie says is true, there’s a teacher out there who once upon a time dismissed Christopher Wallace as a lost cause. I’ve made it my solemn vow to never be that teacher to any student. Public education isn’t a one-size-fits-all situation. Talent and potential come in countless forms, and it’s my job to detect it, then guide it, then help it grow. A teacher who couldn’t see that Christopher Wallace was the Notorious BIG…I cannot imagine a more-appalling indictment against our profession.

25 years later, and the murder of Biggie Smalls remains unsolved. Whoever fired that fatal bullet might still walk among us, knowing he got away with it. Biggie was just 24 when he passed. Today he’d be 50. In 2017, Biggie’s mother, Voletta Wallace, said, “He was so young, so talented, and his life was taken far too soon.”

While Tupac seemed to thrive on the idea of a bicoastal rap war, I truly believe Biggie didn’t want it. When Shakur died, Biggie’s estranged wife, Faith Evans, said, “I remember Big calling me and crying. I think it’s fair to say he was probably afraid, given everything that was going on at that time and all the hype that was put on this so-called beef that he didn’t really have in his heart against anyone. I’m sure for all he thought, he could be next.”

Don’t get me wrong: Biggie was a rough-and-tough guy. Biggie was a criminal. And he didn’t write Walt-Disney songs. Not even close. Yet, when I listened to his lyrics, I always sensed a soul-deep desire for the good life…back of the club/Sippin Moet is where you’ll find me…

When Biggie died, the usual slew of conspiracy theories made the rounds. It was staged. He’s still out there. Him and Tupac played us all. This sort of thinking was certainly helped along by the fact that the album released shortly after his passing was eerily-titled Life After Death (which followed the also-eerily-titled Ready to Die). The album’s cover showed Biggie in a long black coat leaning against a hearse. He wasn’t smiling. He wasn’t mad. It was what it was. But what sticks with me most about that album is a line in the song “Kick in the Door,” Your reign on top was short like leprechauns.

Looking back, such conspiracy theories were a way for us to cope. I recognize that now. The world’s greatest rapper was cut down in the prime of his life, and we lacked the sophistication to properly process all that was lost. But he was so much more than just a rapper. He was a son. A husband. A father. Or, as he would put it, My daughter use a potty so she’s older now/Educated street knowledge I’ma mold her now. Biggie didn’t deserve to die the way he did, when he did.

But maybe, just maybe, this tragic tale has a happy ending. Maybe our crazy conspiracies are actually true, or sort of true. Maybe Biggie Smalls is still out there living his best life after death. Maybe he’s lounging on a private beach in a parallel universe. Maybe that fatal bullet missed its mark on March 9th, 1997. Maybe there never was an East Coast vs West Coast Rap War. Maybe It was all a dream.

In one of my English classes, there’s a kid named Angel. He’s not a traditionally-good student. He frequently blows off assignments. He gets in trouble…a lot. But Angel has a dream. Angel wants to be a world-famous rapper, and he works nonstop at it. He’s always busy thumbing lines and lyrics into his iPhone. His “stage” name is “AngelFromNE.” He tells us to “Stream AngelFromNE on all platforms.” So, one day, I did just that. I streamed AngelFromNE, and listened to a few of his tracks. He’s very raw, but there’s potential there.

When I saw him again, I said, “Angel, you need to read everything you can get your hands on. All the great ones know words. They use words to tell their story. They find a way to make unrhyming words rhyme. You have to be able to manipulate the language.” Then I asked Angel, “You know about Biggie?”

“Not really,” he said. “Biggie’s before my time.”

“Okay,” I said. “There’s this song I think you should Google.”

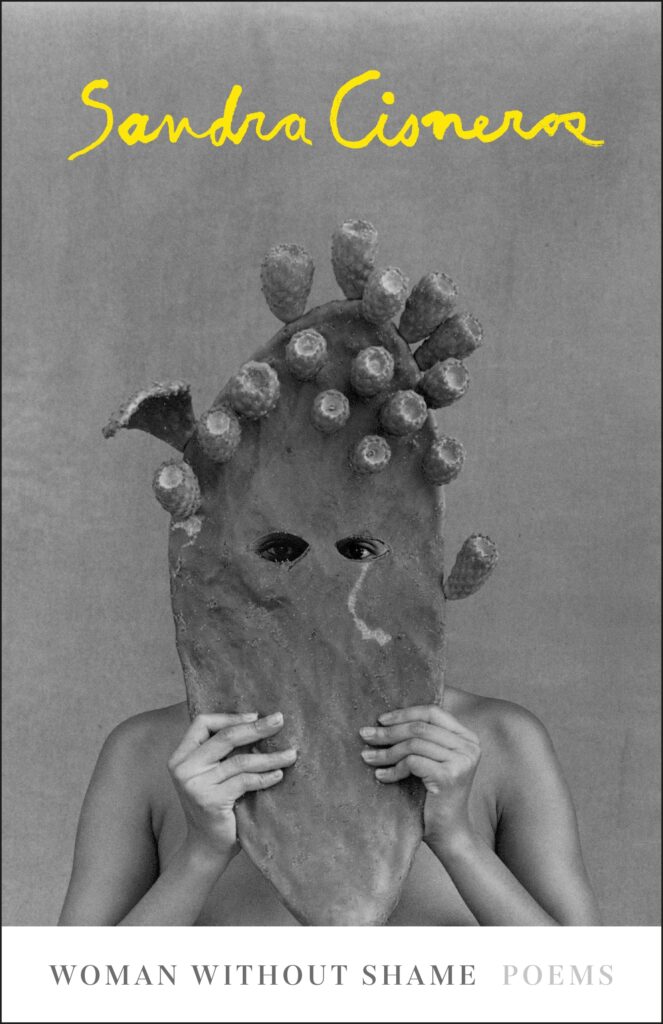

Sandra Cisneros’s Woman Without Shame

Author of House on Mango Street and a dozen other books, Sandra Cisneros has published a collection of poems for the first time in twenty-eight years. Woman Without Shame, published by Knopf, details Cisneros’s journey to embracing her identity as a woman and an artist through song, elegies, and declarations. Using both Spanish and English, Cisneros is both blunt and humorous in her collection.

Sandra Cisneros is currently traveling all over the US, and she will be coming to the Poetry Center in Tucson, AZ, November 9-12. Find a complete list of locations here!

Glorious . . . Cisneros candidly ticks through past lives and lovers with an approach that isn’t concerned with what people will think. . . . As in her former works, Cisneros masters scene-setting, and story, usually with a humorous angle. . . . Woman Without Shame is brave and beautiful.

Meredith Boe, Chicago Review of Books

Sandra Cisneros has won numerous awards throughout her long career as a writer: the Before Columbus Foundation’s American Book Award, the Mountains & Plains Booksellers’ Award, and others. To learn more about her, visit her website.

These lush, narrative-lyrics are written with a vivid wild girl spirit, filled with unbridled love, angst and joy! This book is a page-turner and should not be missed!

Marilyn Chin, author of Portrait of the Self as Nation

To purchase Woman Without Shame, go here.

Superstition Review Submissions Open

Superstition Review is open to submissions for Issue 30! Our magazine is looking for art, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Read our guidelines and submit here.

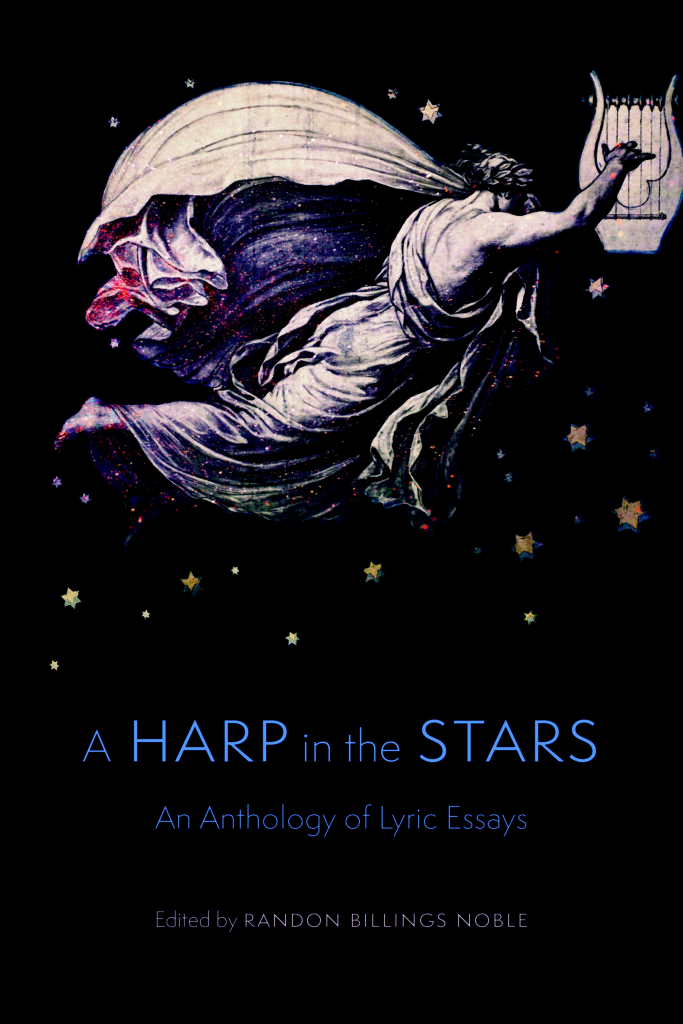

Edited by Randon Billings Noble

Randon Billings Noble has compiled a diverse array of writers for a remarkable collection of lyric essays published by the University of Nebraska Press in October 2021. A Harp in the Stars: An Anthology of Lyric Essays “show lyric essays rely more on intuition than exposition, use image more than narration, and question more than answer.” Although no one summary can begin to capture the essence of these essays, one can expect revelation through flash, segmented, braided, and hermit crab forms, plus a section of craft essays. This collection also features a number of past SR contributors including Dinty W. Moore, Lia Purpura, Sarah Einstein, Elissa Washuta, Julie Marie Wade, Eric Tran, Heidi Czerwiec, and Michael Dowdy.

Randon Billings Noble was featured in Issue 11. If you would like to see even more of Noble’s work, it is featured on her website and she can also be found on Twitter.

I’ve been searching for a book like this for over twenty years. Its remarkable dazzle–a sharp, eclectic anthology combined with whip-smart craft essays–carves out a fascinating look into the bright heart of what the lyric essay can be.

Aimee Nezhukumatahil, author of World of Wonders

A Harp in the Stars is available via the publisher, Amazon, or anywhere books are sold.

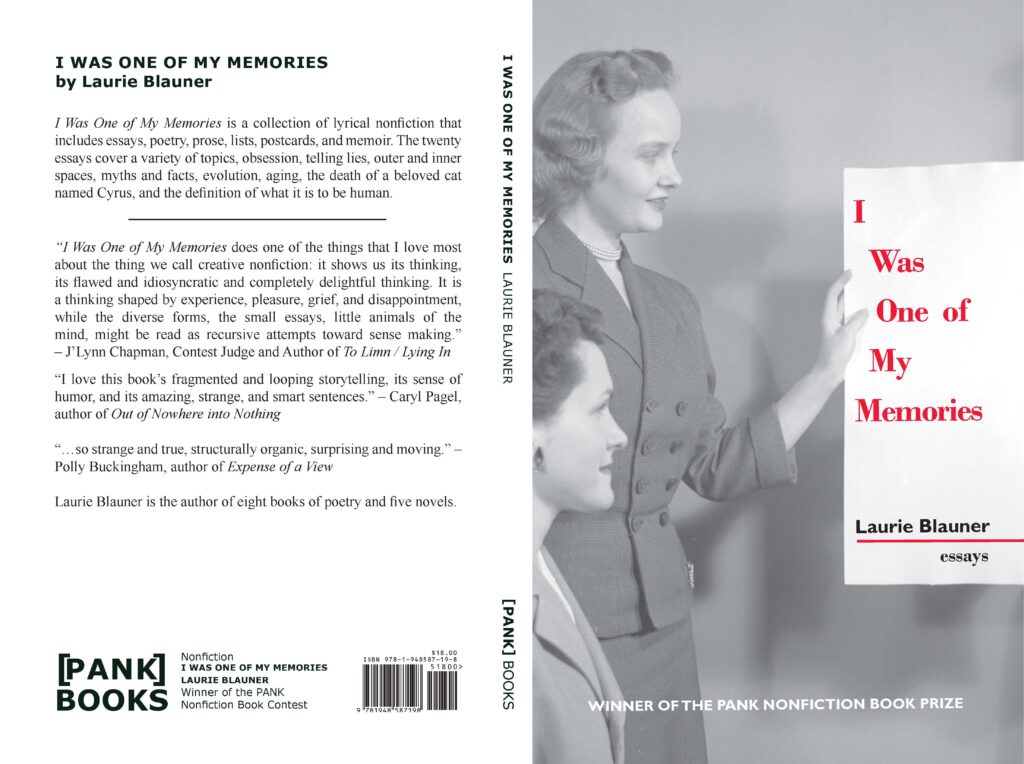

Laurie Blauner’s Two New Works

Congratulations to Laurie Blauner for releasing a new novel and a book of short stories. Her latest novel is titled Out of Which Came Nothing. Enter a parallel universe with Aaron, a boy wholly dependent on religious cult caretakers in this stunningly lyrical and descriptive world. This novel was published in September 2021 by Spuyten Duyvil and is available now on their website and Amazon.

The sense is almost one of a world somewhere between a fairy tale and a fever dream; a nightmare with ill-defined limits that is both all-encompassing and self-contained. This is not a contradiction by any means. It is a state of being that is as specific as a recurring nightmare we can’t let go of, a nightmare that takes over our being and drags us deeply into a well of consciousness where voices in the darkness are threatening to follow us into an uncertain darkness. And we go. Because we have no choice not to.

Misfit Magazine

Laurie Blauner’s newest release, I Was One of My Memories, is an essay collection published by PANK magazine since winning its 2020 Nonfiction Book Award. In this book, you will find more of her lyrical prose as she covers topics such as obsession, lies, aging, and what it really means to be human. You can order this book from PANK.

I Was One of My Memories does one of the things that I love most about the thing we call creative nonfiction: it shows us its thinking, its flawed and idiosyncratic and completely delightful thinking. It is a thinking shaped by experience, pleasure, grief, and disappointment, while the diverse forms, the small essays, little animals of the mind, might be read as recursive attempts toward sense making.

J’Lynn Chapman, Contest Judge and author of To Limn / Lying In

You can find Laurie’s contribution to Superstition Review in Issue 21, which features one of the essays in I Was One of My Memories under the same title, and Issue 8, which features her poetry. You can also check out these books and more on her website.

Mirrors and Doors with Patricia Ann McNair

An Authors Talk

“Reading to relate is like looking in a mirror; I want to walk through a door.”

In this insightful Authors Talk, Patricia Ann McNair delves into the idea — and issue — of readers and writers only finding value in work they can relate to.

Many times she has heard the phrase, “I can’t relate,” from students and peers in regards to stories. As readers, it can be easy for us to become uncomfortable when confronted with stories that we cannot relate to and we cannot understand, but Patricia argues that it is exactly these stories we need to be reading.

When we read only stories we can understand, we are simply looking in a mirror; but, when we read stories that do not resemble our own, we are shown through an open door into a world we never would have encountered before.

“Write what you don’t know….”

Listen to her full Authors Talk below.

Check out Patricia’s newest work, Responsible Adults, coming out in December of 2020 (Cornerstone Press).

Learn more about Patricia here.