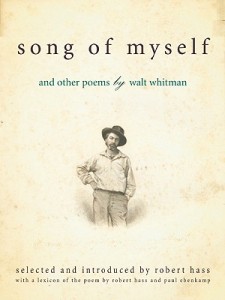

I was gonna write about making stories in second grade with my spelling words. I was gonna write about how my mama, who grew up abjectly poor and who didn’t go to college herself until she was forty-seven, understood so well that she gave me Walt Whitman when I was nine–A child said What is the grass?-– and the collected William Carlos Williams when I was twelve. I was gonna write about loving Wittgenstein, that space between the name and the thing he explores, that space I think we inhabit as artists. The power of story, poetry as prayer, how teaching reminds me every day of how miraculous the language we use to live in this life–I had written 500 words.

I was gonna write about making stories in second grade with my spelling words. I was gonna write about how my mama, who grew up abjectly poor and who didn’t go to college herself until she was forty-seven, understood so well that she gave me Walt Whitman when I was nine–A child said What is the grass?-– and the collected William Carlos Williams when I was twelve. I was gonna write about loving Wittgenstein, that space between the name and the thing he explores, that space I think we inhabit as artists. The power of story, poetry as prayer, how teaching reminds me every day of how miraculous the language we use to live in this life–I had written 500 words.

Then Boston blew up.

And West, Texas.

I quit watching the news years ago, but I stalked Facebook, texting people I know and love in the Boston area. I heard snippets of the working-class drawls of people on the streets in Texas. And I cried.

One sweet-faced freshman at the small liberal arts college where I teach in Virginia, shifted from foot to foot in my office, saying he had family in Boston, asking if he could keep his phone on vibrate.

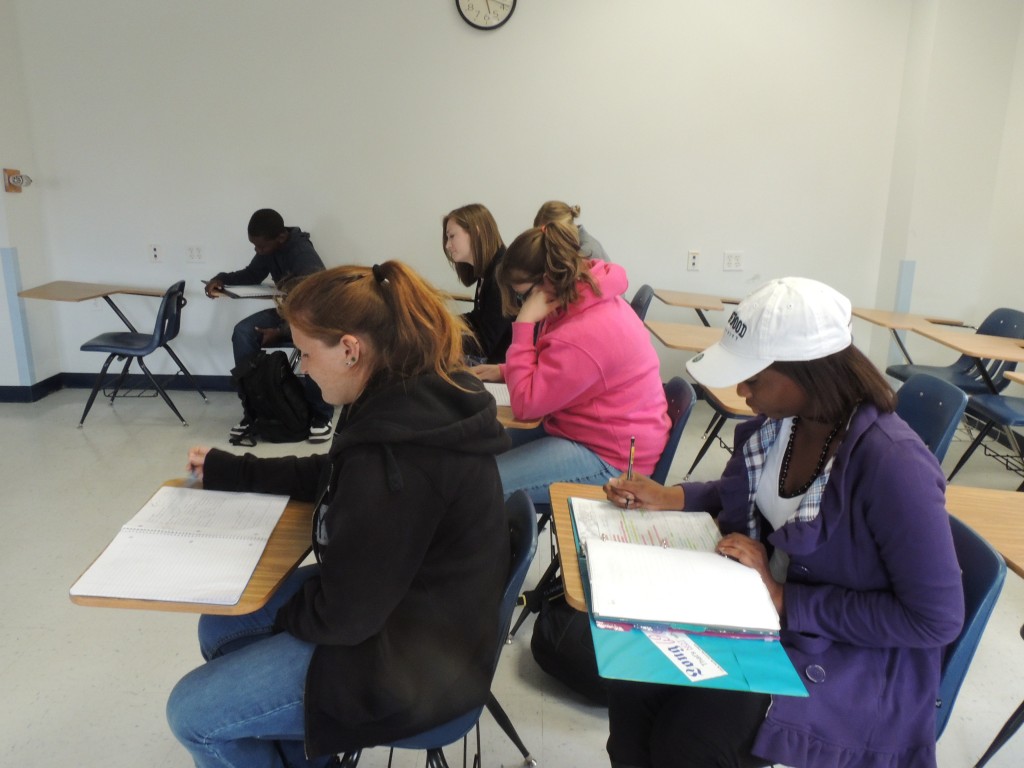

Other freshmen–wide-eyed and curious and scared–in my American Lit class the next morning, discussed Whitman’s Song of Myself–”What is removed drops horribly in a pail”–as a manhunt locked my Boston friends in their homes, keeping their children home from school, away from windows and doors.

Other freshmen–wide-eyed and curious and scared–in my American Lit class the next morning, discussed Whitman’s Song of Myself–”What is removed drops horribly in a pail”–as a manhunt locked my Boston friends in their homes, keeping their children home from school, away from windows and doors.

Shelter in place.

My students asked me Why and I didn’t have an answer. I said, “He’s your age, the one they’re chasing. Can you tell me why?”

They didn’t have an answer either.

What we did have was pain, fear, the shared understanding of how vulnerable we all are. We talked about that vulnerability, and they revealed to me that they, these children who were only six years old when planes hit the Trade Towers, feel that vulnerable, that defenseless, all the time.

One, a girl, generally giggly, who reminds me of a sparrow, bit her bottom lip and, said, “We know how much there is to lose.”

Yes, they do.

They were first-graders, carrying lunchboxes and crayons and Pokemon trading cards, when our military went into Afghanistan They barely remember when we haven’t been at war in the Middle East.

They were in middle school when the economy tanked. They’ve seen their parents lose jobs; they’ve packed up their picture books and soccer gear to move out of their childhood homes as a result of job loss or foreclosure. Some of them have learned what it means to be hungry, to be without heat or healthcare, what it means to make do. And to do without.

I, like lots of other people, have lived or still live in these kinds of truths, but for these kids, this is new.

Many of the kids I teach are from northern Virginia, growing up in the shadow of DC, in those belt-lines of power, in a culture accustomed to not only financial security, but to the security of government work. They are, for the most part, sheltered by their DOD and corporate parents, more so than the kids I taught at a large state school before this. Sending them to our mostly residential university in rural Virginia is, for a lot of them, a continuation of their parents’ desire to protect them.

I’m not judging any of this. It is what it is. But much of the work I do with them, coming from my own poor and rural background, is simply helping them understand, through writing, through literature, that not everyone lives the way they do, in this country, or elsewhere.

I teach as a writer. It’s how I live in the world, and I simply don’t know how to be anything else. I work at a teaching institution; everyone teaches General Education classes, and I love teaching those brand-new-just-out-of-high-school freshmen more than I can say. Even when one of them asks, every semester—

I’m a Bio-PoliSci-Business-Anything-but-English major. What does this class have to do with me?

I tell them, as best I know how, what literature, all art, means to me, and why I think it matters to them.

For me, it is only in literature, in art, that we hear and can intimately know the individual human voice. I tell them that, to my mind, the literature we read belongs much more to them than it does to us, the writers who create it. We, I believe, are reflectors, and in fifty years, the literature created by their peers will reveal their time, their dreams, their fears and values, the hopes they hold close to their hearts. .

Without apology for the tears this discussion always brings, or for what I know many of my own peers will dismiss as sentimental, I tell these young people, that for me the function of all art is to allow us to look across the room at another human being, at each other, and say You are not alone.

We felt alone that day.

As Boston’s police force sought a broken young man their age, and as the death and injury toll rose outside the fertilizer plant in West, Texas, and as the media bombarded the airwaves with conflicting and frightening partial stories, one of my students quietly said, “You know, at first I was kinda pissed at having to read a fifty page poem.” He leaned back, arm thrown over the back of the desk, sprawled in the seat like a young strong animal. Then he smiled. “But, yeah, I really like this Whitman guy.”

I asked, as I do at the beginning of any reading discussion, “So…what struck you? What didn’t you like? What part stayed with you?”

He gave us a page number and we turned to the part he selected, reading it, gratefully, together.

“The city sleeps and the country sleeps,

The living sleep for their time, the dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife and the young husband

sleeps by his wife;

And these tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them,

And such as it is to be of these more or less I am,

And of these one and all I weave the song of myself….”